Mike McGrath spent five years and nine months as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. He was captured after a failed reconnaissance mission sent his aircraft to the ground. His captors transported him to the Hanoi Hilton where he endured a life of isolation, torture and misery. The beatings were frequent and the living conditions deplorable. As the war came to an end, Mike and other prisoners who survived were released. The images etched in Mike McGrath’s memory from his time spent in Hanoi were put to paper and published in the book Prisoner of War: Six Years in Hanoi. The following drawings and excerpts are from that book.

-

On June 30, 1967, I took off from the deck of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Constellation, CVA-64, on my 178th mission, an armed reconnaissance mission over North Vietnam. After bombing a small pontoon bridge, I picked out a second target. "Busy Bee rolling in," I said, as my wingman circled to watch my run. Suddenly there was a muffled explosion. My controls went slack as my A4-C Skyhawk began to roll uncontrollably. I could see the earth rising to meet me. Instinctively I pulled my ejection handle. The quick decision saved my life, but almost immediately after I landed on the ground, Vietnamese farmers and local militia jumped on me. One man held a rusty knife to my throat, while the others savagely ripped and cut away my clothing. It seemed as though they had never seen a zipper; they cut the zippers away instead of using them to remove my flight clothing. One man, in his haste to rip off my boots, managed to hyper-extend my left knee six times. Every time I screamed in pain, the rusty knife would be jabbed harder into my throat.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Within ten hours of my capture, I was en route to Hanoi. At a pontoon bridge, I was taken out of a truck and jammed into a narrow ditch. The soldiers who were guarding the bridge took turns to see who could hit my face the hardest. After the contest, they tried to force dog dung through my teeth, bounced rocks off my chest, jabbed me with their gun barrels, and bounced the back of my head off the rocks that lay in the bottom of the ditch.

I said my final prayers that night, because I was sure I would not reach Hanoi alive.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

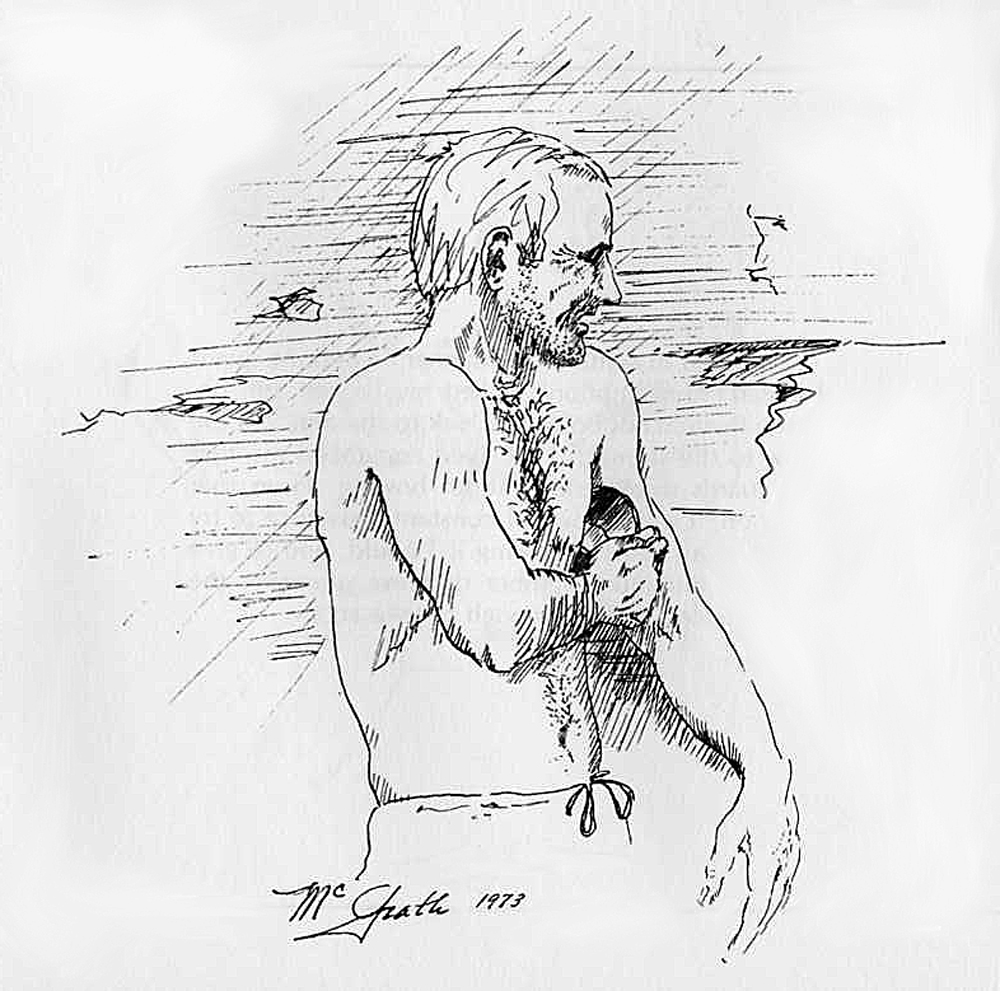

Immediately after my arrival in Hanoi, I was taken to the New Guy Village, a section of the Hanoi Hilton, where new arrivals were tortured and interrogated. I was denied medical treatment because I would not give any information other than my name, rank, serial number and date of birth - the only information required by international law.

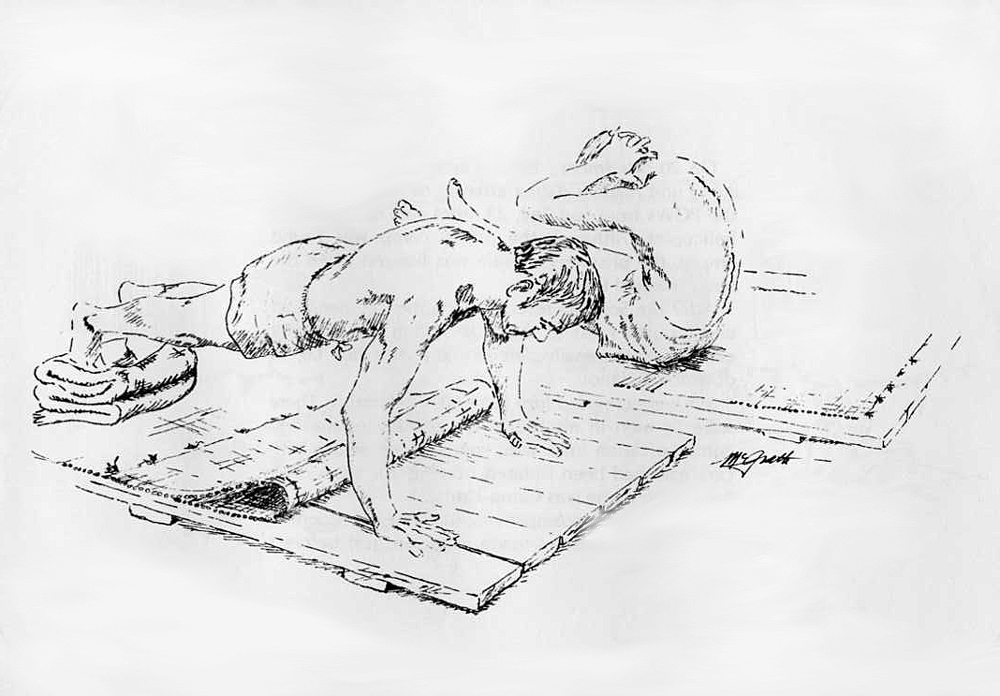

I was delirious with pain. I was suffering from a badly dislocated and fractured left arm, two fractured vertebrae and a fractured left knee. The Vietnamese dislocated both my right shoulder and right elbow in the manner shown in the drawing.

I wished I could die! When the Vietnamese threatened to shoot me, I begged them to do it, Their answer was, "No, you are a criminal. You haven't suffered enough."

Credit: Mike McGrath -

I begged the Vietnamese to set my broken arm and relocate my dislocated shoulder. My requests were ignored. I then begged them to let another American come into my room to help me relocate my shoulder. I received answers such as "You have bad attitude. You are black criminal and you deserve to suffer."

I thought the pain would drive me insane. I made a desperate attempt to relocate my shoulder myself by placing my cup under my armpit, and then throwing myself against the wall. I failed.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Countless hours were spent in this position as we "cleared the hallway" for guards. Each man gladly took his share of clearing, because the consequences of getting caught while communicating could result in torture and months of a miserable existence in irons or "cuffs."

All the POWs became "peekers" as we followed the daily activities around camp. Everything from the movement and interrogation of prisoners to the obscene acts committed by the guards with animals, was noted. The news was quickly passed from room to room in the tap code.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Communications were the lifelines of our covert camp organization. It was essential for everyone to know what was happening in camp, whether the news was about a new torture or just a friendly word of encouragement to a disheartened fellow POW.

The primary means of communication was by use of the "tap code". The code was a simple arrangement of the alphabet into a 5 x 5 block. It was derived through one man's code knowledge gained from Air Force survival school.

The Vietnamese were able to extract, by torture, every detail of the code. They separated us and built multiple screens of bamboo and tarpaper between each room, but they never succeeded in completely stopping us from communicating

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Some men were tied to their beds, sometimes for weeks at a time. Here, I have drawn a picture showing the handcuffs being worn in front, but the usual position was with the wrists handcuffed behind the back. A man would live this way day and night , without sleep or rest. He could not lie down because his weight would cinch the already tightened cuffs even tighter, nor could he turn sideways.

The cuffs were taken off twice a day for meals. If the cuffs had been too tight, the fingers would be swollen and of little use in picking up a spoon or a cup.

Hopefully, a man could perform his bodily functions while the cuffs were momentarily removed at mealtimes. If not, he lived in his own mess.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Many men were handcuffed or tied to a stool as a means of slow torture. The POW sat in one position, day and night. Each time he would fall over, the guards would sit him upright. He was not allowed to sleep or rest.

Exhaustion and pain take their toll. When the POW agreed to cooperate with his captors and acquiesced to their demands, he would be removed. Here, I have pictured a guard named "Mouse," who liked to throw buckets of cold water on a man on cold winter nights.

Some men, in heroic efforts to resist the "V," remained seated for 15 to 20 days. One man made a super-human effort to resist. He lasted 33 days on the stool before giving in!

Credit: Mike McGrath -

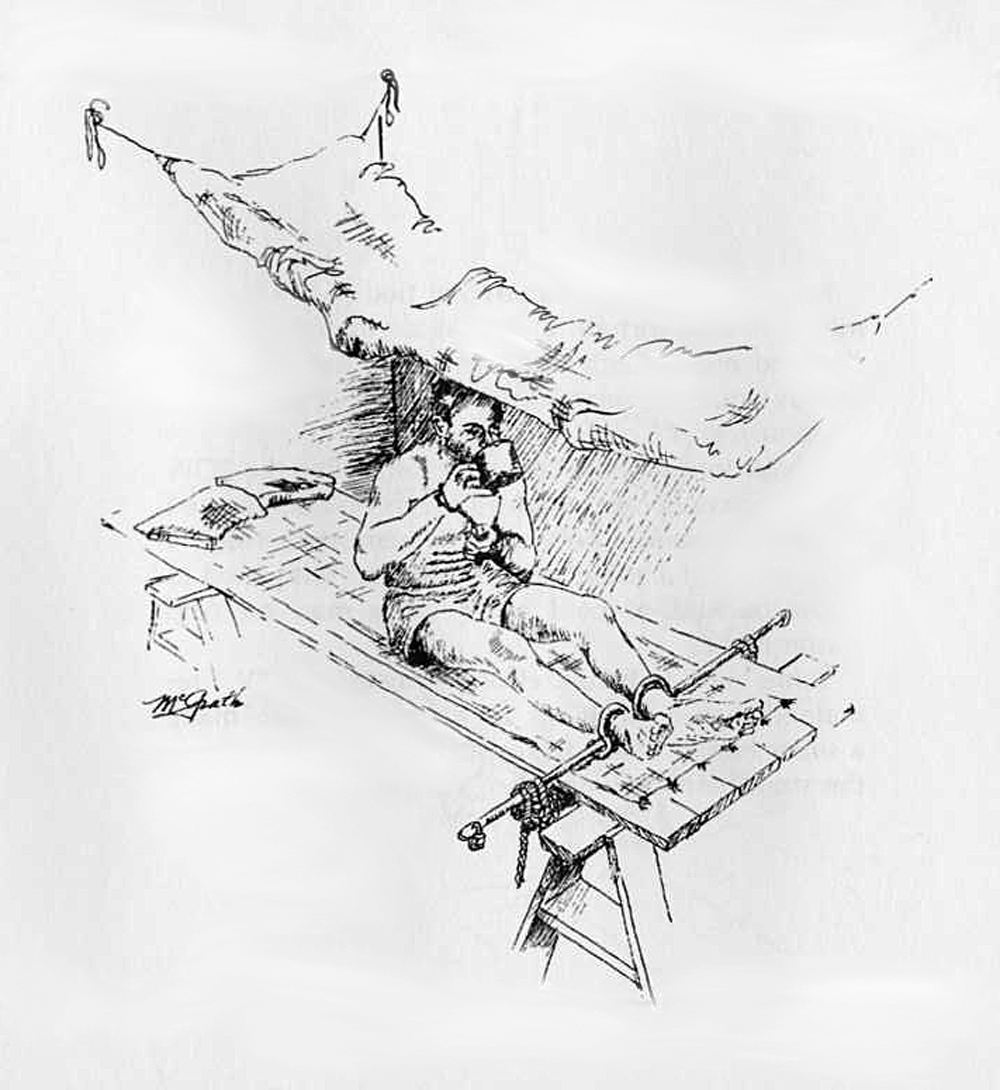

Here, I tried to depict the "Vietnamese rope trick." The arms are repeatedly cinched up until the elbows are forced together. Sometimes at this point the "hell cuffs" are applied. The "hell cuffs" are handcuffs which are put on the upper arms and pinched as tightly as possible onto the arms, cutting off the circulation. The resulting pain is extreme. If the prisoner has not broken down by this time, his arms are rotated until shoulders dislocate. Words could never adequately describe the pain, or the thoughts that go through a man's mind at a time like this.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Our normal diet consisted of either rice or bread and a bowl of soup. The soup was usually made from a boiled seasonal vegetable such as cabbage, kohlrabi, pumpkin, turnips, or greens, which we very appropriately called, "sewer greens, swamp grass and weeds." The flavor was very bland because no spices were used. I remember one very bad food period when we had two daily bowls of boiled cabbage soup for four straight months. Occasionally we would find a small chunk of meatless bacon fat in the soup.

Bland side-dishes of cooked vegetables or fish appeared with more regularity during the last two years.

I lost fifty pounds in the first three months of my captivity. Many others lost considerably more. It was not unusual for a man who was over six feet tall to weigh as little as 120 pounds.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

Until 1970, exercising was prohibited. Every attempt was made by the "V" to keep us weak and demoralized. Despite the fact that we did not have adequate vitamins, protein or minerals, and the fact that we always felt tired and hungry, most men ignored the camp regulations and continued a daily exercise program. Many men give their strenuous exercise program as the reason for their good health. Sickness, such as hepatitis, could strike at any time, and it paid to be in best physical condition possible to cope with disease.

Credit: Mike McGrath -

I was set free on 4 March 1973, and immediately flown to Clark Air Force base in the Philippines. Hot showers, steaks, peanut-butter sandwiches and thousands of smiling faces were on hand to welcome me back.

On 7 March 1973, I returned to San Diego, California, where I was greeted by my wife, Marlene, and our two sons, John Jr. and Richard. In the drawing I tried to express all the joy and happiness my heart felt in that reunion. The years of waiting for this moment were suddenly forgotten. Then I realized how great it was just to be alive, to be wanted and loved, and most of all, to be an American.

As so many of my friends and comrades said, as they stepped from the giant Air Force C-141s to the land of the free, "God Bless America!"

Credit: Mike McGrath