In the late 1940s, the notion of space travel remained squarely in the realm of science fiction. But at what would soon become Edwards Air Force base in southern California, young Air Force doctor John Paul Stapp paid close attention to the rapidly developing technologies in aviation and rocket science, and saw no limit to how far mankind could go—or the potential dangers pilots might face. Browse a gallery of the U.S. Air Force's high-altitude balloon experiments and the researchers, scientists, and test pilots who made them possible.

-

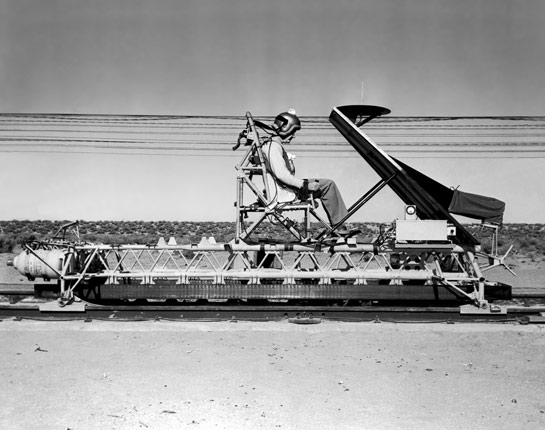

When U.S. Air Force Captain Dr. John Paul Stapp began experimenting with rocket sleds, like this one from 1954, many scientists believed the maximum force humans could withstand was 18 times the pull of gravity, or 18 g.

Credit: Edwards Air Force Base -

On December 10, 1954, Stapp's sled, propelled by nine rockets, flew down the track at more than 630 miles per hour and came to a full stop in 1.4 seconds. Stapp withstood a record-breaking 46.2 g.

Credit: National Aerospace Training and Research Center -

During his December 1954 rocket sled experiment, Stapp’s eyes hemorrhaged, leaving him temporarily blind. Pictured here is a series of images taken from inside Stapp’s sled during one of his experiments.

Credit: U.S. Air Force -

Beginning in the 1940s, Dr. Stapp also studied man's experiences with zero gravity, which typically caused severe nausea. Stapp discovered a solution to this problem, which had been a significant blocker to the potential of space travel.

Credit: National Aerospace -

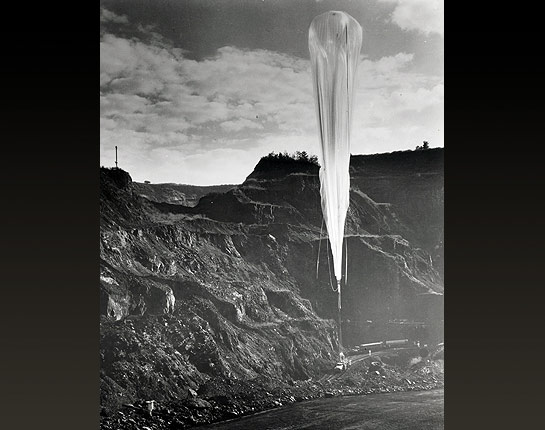

At Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, Dr. David Simons had been conducting atmospheric experiments with animals, sending them to altitudes over 100,000 feet in small, durable gondolas suspended with balloons -- like the one depicted here. In 1955, Dr. Simons was recruited to Stapp's team to investigate "the human factors of spaceflight."

Credit: National Aerospace Training and Research Center -

Vera Winzen (pictured) and her husband Otto (not pictured) made the balloons for Stapp’s experiments. Their company pioneered a new process to create balloons large and strong enough, yet still light enough, to bring a human and their equipment into the stratosphere.

Credit: David Simons -

At the Winzen factory, "Balloon Girls" worked in stocking feet and clipped their fingernails every morning to prevent any accidental snags or tears in the delicate balloon material, which was .002 inches thick.

Credit: General Mills Archive -

Air Force engineers developed gondolas to safely carry a scientist and their equipment at high altitudes for an extended period of time. Here, Dr. Simons sits in a gondola and looks through the window while preparing for Project Manhigh.

Credit: RavenAerostar -

On August 19, 1957, Simons set out in his new balloon, pictured here. He was prepared to spend at least 24 hours monitoring his vitals and performing meteorological and astronomical experiments high in the earth's atmosphere.

Credit: National Museum of the United States Air Force -

Simons set an altitude record of nearly 102,000 feet during his 32-hour balloon flight. Here, Major Simons photographed himself near the peak of his climb.

Credit: National Museum of the United States Air Force -

Simons captured a photo of the horizon at sunset during his balloon flight on August 19, 1957, during which he observed that, at that altitude, the stars did not twinkle. In 1958, NASA began operations and took over all space flight experiments.

Credit: United States Air Force -

Simons radioed back to the ground crew that he had a "ring-side view of the heavens." He later recalled, " Where the atmosphere merged with the colorless blackness of space, the sky was so heavily saturated with this blue-purple color, that it was hard to comprehend."

Credit: United States Air Force -

In 1958, Stapp and the USAF began Project Excelsior to create and test a new multi-stage parachute for high-altitude evacuations. He chose Capt. Joseph Kittinger (pictured) as his test pilot.

Credit: National Museum of the United States Air Force -

On August 16, 1960, Kittinger, outfitted in a pressure suit, heating apparatus, and double-release "drogue" parachute, took "the Highest Step in the World" when he leaped from his gondola at 102,800 feet above the earth.

Credit: United States Air Force -

Kittinger reached a speed of more than 600 miles per hour during his fall and landed safely back on earth after falling for 13 minutes and 45 seconds. The new parachute technology would save the lives of pilots needing to eject from high altitudes, including an incident in 1966 when an Air Force officer's plane came apart at 83,000 feet.

Credit: National Museum of the United States Air Force