American Experience

“Bombshell”

HARRY S. TRUMAN (archival):

A short time ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima and destroyed its usefulness to the enemy.

JANET BRODIE:

There was such/ delight in the bomb, the atomic bomb and it had ended the war and this would be our major weapon.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

A number of polls asked Americans, "Do you approve of the use of the atomic bombs?" And the answer was, "Yeah." There was a small number of people who really wished that more atomic bombs could have been dropped on Japan.

NARRATION:

America’s first impression about the bomb -- no matter the news source -- comes from press releases written by a single journalist working undercover for the War Department.

WILLIAM L. LAURENCE (archival):

I saw a world blow up in a burst of cosmic fire / and a new one, born from its ashes.

BEN YAGODA:

A lot of the coverage was as if it was like a gigantic, gigantic conventional bomb, / just much more powerful than the ones that had been used before. / There was relatively little written about the radiation.

VINCENT INTONDI:

As long as we're talking about getting atomic rings in your cereal box or / school mascots, we're not thinking about skin falling off of human beings. We're not thinking about / ‘could that happen to us in an arms race?’

NARRATION:

As the U.S. and Soviet Union compete for nuclear supremacy, the Truman administration downplays the weapon’s poisonous radioactive effects to shore up public support for the bomb.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

You want them to think that nuclear bombs are okay.

NARRATION:

A few journalists look beyond the propaganda to raise ethical concerns the government does not acknowledge.

WILFRED BURCHETT’S VOICE (archival):

I felt staggered by what I’d seen. I write this warning to the world.

NARRATION:

But the government fights back, to re-establish its version of the story.

THE BEGINNING OR THE END (archival):

More than an end to war, we want an end to the beginnings of all wars.

And if the bomb shortens the war, it will save many thousands of American lives.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

These initial narratives that get set up between 1945 and 1947, these are still the terms in which people, by default, talk about the atomic bomb to the point where if you tell somebody this narrative, they'll say, right, that's the story, right? And, in many ways, it's not true!

ACT I SCENE 1

NARRATION:

By 1938, Adolph Hitler is consolidating Nazi power in Germany, and marshaling the force needed for the Nazis to control all of Europe. Hitler’s intentions on the battlefield are clear.

Less obvious but just as important, German and Austrian scientists split a uranium atom in two. The process called Fission, gives Germany a head-start toward a new type of weapon— the atomic bomb.

ARCHIVAL:

The nucleus explodes, giving off dangerous radiations and heat.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

When you split atoms you're left with these two half atoms and they are intensely radioactive. / By the end of the 20’s people know that radiation equals death. And it's a horrible death. It's a wasting death.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

This is the first time an atom has been broken in two. But almost no one paid attention to fission when it happened in December of ‘38.

LAURENCE (archival):

This new model, however, the scientists are talking about…

NARRATION:

One of the few paying close attention is New York Times science writer, William Leonard Laurence.

WILLIAM LAURENCE (archival):

It may be said that the Atomic Age is here to say. The question is: are we?

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Laurence is excited when there are reports coming out of Germany that chemists have split the Uranium atom.

He makes that front page material for the New York Times.

Laurence thought this is amazing. This could be a source of energy. But he also thought that maybe it could be used as a weapon.

The Germans have extremely good scientists, they're on a war footing, and they're very good at organizing large scale projects.

NARRATION:

Afraid of Germany’s nuclear intentions, in August 1939, Hungarian, physicist Leo Szilard visits Albert Einstein on Long Island. The leading scientist of his day, Einstein signs Szilard’s letter urging President Franklin D. Roosevelt to create an American atomic weapons program.

The letter convinces Roosevelt to establish a secret Advisory Committee on Uranium. Though publicly, he pledges the U.S. will stay out of any European conflict.

FDR (archival):

This nation will remain a neutral nation… But even a neutral has a right to take account of facts.

HITLER (archival):

Mr. Roosevelt demands that German troops shall not attack the following independent nations: Poland, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France

NARRATION:

By 1941, on the opposite side of the globe, Japanese military aggression has led to the takeover of all Manchuria and brutal control of other parts of Asia.

Hitler welcomes Japan’s foreign minister in Berlin to celebrate the two country’s alliance as Axis powers.

And in December 1941, / Japan reveals it has designs on more than just Asia.

ARCHIVAL:

We have witnessed this morning the severe bombing of Pearl Harbor. It is no joke. It is a real war.

FDR (archival):

December 7th, 1941, a date which will live in infamy.

NARRATION:

When the U.S. enters the war, the Germans have a 3-year lead in the race to build an atomic bomb. Roosevelt gambles $2 billion to build the weapon before the Germans do. This secret science experiment is known by its code name: The Manhattan Project.

NARRATION:

It will be headed by an ambitious officer from the Army’s Corp of Engineers.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Leslie Groves is first and foremost an engineer.

He made his reputation in building the Pentagon. He built the Pentagon ahead of schedule and under budget.

o/c

GREG MITCHELL:

Groves had really wanted to join the war effort. And he was disappointed that he never got that.

So when he was asked to lead the bomb project, this was a dream come true for him.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Leslie Groves saw the Manhattan Project as an industrial project, not a scientific project.

There were scientists involved, but it was really about industry.

NARRATION:

To direct the project’s scientific research, Groves chooses a 39-year-old physicist from Berkeley, California, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

JANET BRODIE:

Groves shocked people when he chose Oppenheimer, but it was a brilliant appointment. Oppenheimer could keep in his head the incredible complications of the science, but also handle the people.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

The biggest tool they had for keeping the Manhattan Project secret was taking all of the scientists who had worked on the subject and putting them under government oaths and secrecy arrangements.

That deprived journalists of stories that they might have written about atomic bombs or something like that. And the journalists noticed this.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

At the New York Times, William Leonard Lawrence had a very good idea of what was going on. He had been putting together bits of string for months.

NARRATION:

Years later, Laurence would recall his early suspicions…

“I noticed a strange phenomenon. I would come to a meeting and a couple of top scientists who had always been there were missing. I would call up their universities and I would get evasive answers. They weren't there, we don't know, or they're not coming back.”

MICHAEL GORDIN:

William Leonard Laurence was born in Imperial Russia and then he moves to the United States.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

He talked his way into Harvard, but he was caught up in a cheating scandal and never earned a degree.

He came to New York and fell into a job at the New York World that was very sensationalistic.

It was a great home for Laurence who had wanted to be a playwright and had a great flair for drama. He wrote several stories about a researcher who claimed to have disproven Einstein's theory of relativity.

The New York Times saw this story, hired him away and promoted him publicly as the first daily science writer, which meant that he was under pressure to be constantly producing science stories.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Laurence is part of a group of journalists who collectively win a Pulitzer Prize for creating this field of science journalism.

Laurence had come to Groves’ attention, not in a positive way. He came to Groves’ attention because he was writing stories about atomic energy, and Groves didn't like that. Groves didn't want anybody to be writing about these matters.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Laurence ached to write more about atomic science, atomic power. But he was frequently shut down by the government.

But both he and the Times went along with that because they needed to be on the team to promote victory in this total war.

ACT I SCENE 3

VINCENT KIERNAN:

World War Two was seen as a live or die affair for the United States. And given that total commitment, journalists found themselves on the team.

BEN YAGODA:

They were eating the same food under the same fire, wearing the same clothing and uniforms and helmets as the people they were covering.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

They wouldn't do anything that would jeopardize America's chances of winning. That meant that they went along with a voluntary code of censorship.

NARRATION:

The press corps in Europe includes 30-year-old freelancer John Hersey…

KAY CALLISON:

Hersey was overseas as a war correspondent. He worked both for Time and Life. Hersey had been covering the Italian campaign. He'd seen war ruins. He had seen terrible destruction, he'd covered war from all different perspectives.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

Near the end of the war, he had already covered a lot of combat, and he had published a novel that won him a Pulitzer Prize.

BEN YAGODA:

Hersey, under obviously difficult conditions, just did remarkable work.

NARRATION:

And in the Pacific theater, the Cleveland Call & Post editor, Charles Loeb, embeds with segregated troops as a pool reporter and photographer for the Black Press.

FELECIA ROSS:

Charles Loeb logs more than 4,000 miles.

He goes to Okinawa, to Guam, covering the activities of the 93rd unit, the all-Black unit.

The Black community, they get to see how their son, or their brother, or their husband is doing. It gives them a sense of pride.

CHARLES LOEB (Oral History):

One of our functions is to tell the Black side of any story, because the white media still suffers from a lack of believability in the Black community.

NARRATION:

While journalists like Loeb and Hersey cover the war from the frontlines, at home General Groves makes sure that no word about the bomb leaks, especially to the press or even to Congress.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Groves values secrecy. He wants this project controlled, and the basic principle of security is compartmentalization. Everybody knows what they need to know and not need more than that.

ARCHIVAL MANHATTAN PROJECT MAP:

At Oak Ridge, Tennessee, at Hanford, Washington, and at Los Alamos, New Mexico.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

…because there are three big aspects of the project.

One is to separate uranium.

You need to do it in secret, and you need to do it with a lot of electricity. There aren't that many remote places that have a lot of electricity,

but there is one, which is Tennessee, because the Tennessee Valley Authority, produced a huge amount of electricity, and that electricity gets poured into Oak Ridge.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

There's no precedent for something like Oak Ridge. This is genuinely a secret city.

Tens of thousands of people and their families are living there. They have intramural sports leagues of baseball and football. The number of people who at one point worked on the Manhattan Project, is about 500,000 people.

So if you were not a soldier or too old or too young to work, there's about a 1 in 100 chance you worked on the Manhattan Project and probably didn't know it.

FELECIA ROSS:

There were 7,000 Black workers at the Oak Ridge Tennessee plant. They did maintenance work, they did construction work.

And for three years, these workers did not know that they were at a plant that was involved in making the atomic bomb.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Then, when plutonium is discovered and people realize that that could power a bomb, for that you need to have a lot of water, and you need to be isolated. So they put it on the Columbia River in Washington state.

Then you need a place for your bomb designers, and bomb design requires isolation and a lot of very temperamental scientists.

NARRATION:

Oppenheimer, who’d spent time in New Mexico, selects a remote spot in the desert outside of Santa Fe in a little town called Los Alamos. More than 5,000 scientists and their families relocate there.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Groves had a pretty bad relationship with most of the scientists. He regarded them as prima donnas, over-educated eggheads. You didn't want their advice on almost any other thing.

You didn't want them to think about the politics. They were bad at that in his mind.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Los Alamos is a bit of a security risk, because you have lots of scientists talking to each other about work that's going on in other groups on the mesa. Groves tries to restrict that, and Oppenheimer says, “no, we need that. It's important for progress. We have to have that kind of thing happen.”

GREG MITCHELL:

It's hard to believe that the secrets didn't come out.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Groves is afraid Congress would cancel the project if they knew about it, because they wouldn’t understand that this science fiction thing was a good plan. That’s why Groves is committed to keeping so much secrecy.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

General Groves knew that this was going to be, if it happened, a shocking event, and people would have to be prepared for their entrance into a new world, the atomic age.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Starting in spring of 1945, Groves knows he has to manage the public release of it, because the whole point of this bomb is to change the equation.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

What do you tell people about this? What should they know? What shouldn't they know? This becomes a major official goal of the Manhattan Project.

And so they are going to have to shift gears from absolute secrecy to an incredible amount of publicity.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

There's no way to do the publicity of the bomb without somebody who understands some physics because they need to explain it in a way that is both accurate and obfuscating enough so that you don't reveal anything you don't want to.

NARRATION:

Groves knows the right man for the job. He goes to the New York Times with hopes of recruiting its science journalist.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Groves went to William Laurence's editor and behind closed doors asked to use Laurence for a military project of some importance.

WILLIAM LAURENCE (archival):

I was privileged to be tapped on the shoulder by the army and given the assignment that every newspaperman dreams of.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Laurence is plugged in. He knows about the topic. He knows many of these scientists and so they agreed on this relationship with the New York Times to basically loan them William Laurence as a person who would write press releases.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

Journalism was still in the process of developing its ethical code during WWII. For the publisher of the New York Times, the fact that one of their reporters could help with the war effort seemed to override any potential conflict of interest in this dual role.

GREG MITCHELL:

Laurence didn't need any prodding to picture it in the most positive way.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

The Times got a really good deal. Their star science reporter got sole access to all sorts of information that he was able to use for years afterward.

What he did not get was a lot of money. And it remains a source of debate exactly how he was supposed to be compensated, but the bottom line is he largely worked for the Manhattan Project for free.

GREG MITCHELL:

Laurence's main task was to write press releases in the months before the bomb was dropped. They didn't really know when the bomb would be ready to be used and so the need for all these background articles was profound.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Groves gave Laurence great license to go virtually anywhere he wanted to. Doors were unlocked for him that weren't unlocked for other reporters because they knew that he would produce the story that they wanted.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

He describes Hanford as Atom-land-on-Mars. It's so alien it's not even on this planet and that's good. That's progress.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Laurence was effusive, perhaps more effusive than they wanted him to be.

These stories they're wild and wooly and enthusiastic and that is not what these army lawyers who are reviewing them want to see. They tone them way way way down. But for him this is the story of the century. He is the one built to write this story.

NARRATION:

In the spring of 1945, the U.S. suffers a staggering loss: the sudden death of its commander in chief, president Roosevelt. His successor is the little-known Vice President, Harry S. Truman.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Truman was succeeding this historically transformative president, Franklin Roosevelt, who had reshaped the country in so many ways. And Truman was basically a machine politician from Kansas City, Missouri, whose only foreign policy experience was being a GI in World War I.

NARRATION:

As Vice-President, Truman had not even been told of the existence of the Manhattan Project. He first learns of it 2 weeks after taking his new oath.

In Europe, the Allies from the West and Soviets from the East keep advancing on the German capital. When the Soviets take Berlin, the Nazis surrender.

Back home, Americans are jubilant.

But Truman warns them not to celebrate too soon…

HARRY S. TRUMAN (archival):

This is a solemn, but glorious hour.

NARRATION:

…as US forces fight their way from island to island toward Japan.

HARRY S. TRUMAN (archival):

Much remains to be done. The victory won in the West must now be won in the East.

NARRATION:

With the surrender of Germany, suddenly Japan becomes a potential target for the atomic bomb.

PAUL ALKEBULAN:

The Germans quit, but that doesn't mean the war is over.

By the time the Marine Corps got to Iwo Jima, a lot of blood had been spilled.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

We were going one island at a time at considerable cost in lives. And there was talk that Japan was not going to surrender, that we would have to invade Japan itself.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

I think it's hard for people today to project back what it is like after four years of bone-crushing total war, what people are used to in terms of violence and the violence they read about, the violence they hear about.

You have a very battle-weary home population.

MY JAPAN – U.S. Propaganda Film (archival):

We await eagerly and passionately the sacred honor of dying to halt you. We will stop at nothing to crush you.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

The Japanese were represented in American media as a savage horde.

They committed plenty of atrocities. There's no question about that.

But it was almost cartoonish, racist, an often-dehumanizing enemy. And a terrifying one.

PAUL ALKEBULAN:

People were very nervous about the invasion of Japan. This was going to be a long and bitter struggle. When is it going to end? So that was the mood of the country, you know. Glad that victory was in sight. But what were you going to have to do to get your hands on that victory?

POTSDAM CONFERENCE NEWSREEL (archival):

In the closing stages of World War II, a historic conference was called between the leaders of The Big 3 nations of the allies. Harry S. Truman arrived aboard the cruiser Augusta as the replacement for the late Franklin D. Roosevelt.

NARRATION:

Two months after the Nazis surrender, President Truman sails to Potsdam, Germany to meet with his allies and divide up the spoils of Europe between the communist East and the capitalist West.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin wants to gain full control of all Eastern Europe. Truman wants to avoid a similar outcome in Asia.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Truman was in a very difficult place in 1945.

He's in charge of negotiating with Joseph Stalin who has been controlling the Soviet Union for almost as long as Truman has been aware of the Soviet Union.

Truman doesn't quite know where he is. But he knows one thing, which is, he's a person who makes decisions.

NARRATION:

Publicly, Truman asks Stalin to join the invasion of Japan. Privately, he hopes the war ends before the Soviets invade.

GREG MITCHELL:

The Russians were going to sweep in and decimate the Japanese troops and Truman knew that. He wanted to end the war before the Russians got into the war in a big way.

NARRATION:

Meanwhile, the first test of America's $2 billion superweapon is unfolding in the New Mexico desert.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

The Trinity nuclear test was to take place in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

NARRATION:

Truman needs the results quickly to gain leverage over Stalin— if the science works…

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

This was a very tense period. They did not know whether this thing was going to work.

ROBERT WILSON’S VOICE (archival):

Every time we tested some component that had to do with the test it would fail.

ROBERT KROHN’S VOICE (archival):

There had been some speculation that it might be possible to explode the atmosphere in which case the world disappears.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Groves is worried about what happens if there's publicity. He needs to have some kind of account. This is where Laurence is useful.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

So, Laurence wrote a series of press releases of increasing level of mistruth.

ALX WELLERSTEIN:

Release A was an ammunitions dump exploded. There were no problems, no casualties. Move on.

And if you go down B, C, D, increasingly things had gone wrong. And some of them had to be spaces for here's a list of people who are now dead because this was actually a scientific experiment gone awry.

NARRATION:

The test releases energy equal to 21 tons of TNT -- more than four times the power of what had been predicted.

SUSAN EVANS’ VOICE (Archival):

It felt like an earthquake. He got out of bed and he says, "I want you to come look. The sun's rising in the wrong direction."

ELIZABETH INGRAM’S VOICE (Archival):

We were headed up to Albuquerque when we saw this great big flash of light. And my sister, she said, "What happened?"

Reporter: “Was there anything odd about your sister asking about the light?”

“Yes, because she was blind.”

GREG MITCHELL:

Some of these local people from dozens of miles away called their newspapers and said, "What happened?"

VINCENT KIERNAN:

The local papers asked the press office ‘what was going on last night?’ And they provided them with Laurence's lowest level story.

And the local media just accepted that and that's what they wrote.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Laurence does exactly what Groves wants. And he is perfectly happy to work within those constraints.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Laurence's first act of loyalty was an act of lying, an act of mistruth, which is a cardinal sin for a journalist.

GREG MITCHELL:

It was known from the beginning that atomic energy posed risks of radiation. Before the Trinity test, there was much discussion about whether people who live nearby should be notified.

NARRATION:

To monitor the biochemical dangers of plutonium and uranium, Groves had hired Doctor Stafford Warren, a pioneer in the new field of radiology, to be the project’s Chief Medical Officer.

JANET BRODIE:

Stafford Warren is little known, but he was a major medical figure for the Manhattan Project.

As Oak Ridge and Hanford were picking up uranium and plutonium production. They were very concerned but, this sounds so cynical, their concern about the radiation poisoning was to keep the secret of the Manhattan Project.

If all of a sudden, this strange sickness began to emerge from these secret sites, some reporter would reveal what was going on. Warren was good at secrets. Groves appreciated that. So the two worked pretty well together.

NARRATION:

Prior to the Trinity test, Warren's team outlines the dangers of radiation in a memo to Groves.

JANET BRODIE:

They wrote some alarming messages that Groves would have seen.

That memo was basically ignored.

NARRATION:

A few days later, Warren sends a second memo, more to Groves' liking.

JANET BRODIE:

In the following memo, Warren minimized the danger of radiation on the ground.

He said if American combat troops have to be sent into Japan, they're not going to be in danger from radiation. That's certainly what Groves wanted to hear.

Somehow, Warren was able to persuade himself, justify, forget, deny, repress his own fears about the atomic bomb.

GREG MITCHELL:

After Trinity, the scientists went out and tracked the radioactive cloud. They were shocked to find it was spreading for many miles and at a higher levels than they had anticipated.

They soon found farm animals, cattle with hair burned off.

HOLM BURSOM’S VOICE (archival):

An old man, Mac Smith, had a black cat, just as black as the Ace of Spades. That thing had white spots all over it.

JANET BRODIE:

By and large, this huge event escaped public commentary. And I think it speaks to the era. This is wartime. Don't, don’t talk about things.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

So Groves knew that the radiation existed and that it was a problem. But it was not part of the narrative that he wanted to have out there.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

The radiation is the part that people are generally going to grasp onto as the special nature of the weapon. And it's also the one that's associated with the most horror.

Because of the unique health effects of radiation, this puts it in a category more like chemical weapons.

JANET BRODIE:

Groves did not want any association with chemical or biological warfare.

The Germans used poison gas in World War I. Eventually, the British did too.

MARTIN GREENER’S VOICE (archival):

We were frightened by the gas, of course, because we kept spitting it out, and it kept coming up our throats, the yellow stuff, yellow green it was.

JANET BRODIE:

The world was revolted by that kind of warfare. It somehow didn't fit into what was moral in war.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

There's a lot of concern about using it in World War II. Hitler doesn't, the British don't, the Soviets don't, the Americans don't, the French don't.

JANET BRODIE: So, Groves did not want the atomic bomb to be seen in that light.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Groves could see what was coming down the road. They would have a bomb that they could use in war.

NARRATION:

Groves immediately reports to his superiors that the test surpasses all expectations.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

This news went to President Truman at the Potsdam Conference.

He suddenly felt like he was in a place of great security. This influenced how he thought about Japan and the end of the war. He made the Potsdam Declaration a harsher thing than he might have otherwise done.

And it influenced how he thought about the Soviet Union, how he was going to deal with them in the post-war.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

The Americans don't want a divided government. It's an American weapon. It's not a Soviet weapon. And that means the post-war settlement in Japan will look like something rather different than Berlin and Vienna, which are carved up into Soviet, British, French, and American sectors.

JANET BRODIE:

As soon as the Trinity test was a success, there were orders to bring the bomb to Tinian.

NARRATION:

1500 miles off the coast of Japan, final steps are taken to ready and activate the bomb.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Laurence is on the island of Tinian, hoping with all his heart to be on that plane, to be on that mission.

He wanted to be there to see the use of the bomb, but he was not allowed to go. He was almost in tears that he was not allowed to be on. But he had watched it take off, and was waiting for it to come back.

GREG MITCHELL:

There was a photographer for Hiroshima's main newspaper named Matsushige, who was not far from where the bomb went off.

YOSHITO MATSUSHIGE’S VOICE (subtitled):

I pulled my camera out from the rubble and I grabbed my wife’s hand before we dashed out of our crumbling house.

GREG MITCHELL:

He was so sickened by what he saw that he could only push the shutter about half a dozen times.

These are the only photos that survived of that day in Hiroshima, and there was only a handful of them. His photos were seized when the Americans arrived. In 1945, Americans were only seeing the mushroom cloud, destroyed buildings, some of the landscape, and not the human effects at all.

NARRATION:

On August 6th, 1945, the day of the Hiroshima blast, President Truman is returning by ship from the Potsdam Conference. His public announcement is filmed on board.

HARRY S. TRUMAN (archival):

We are now prepared to destroy, more rapidly and completely, every productive enterprise the Japanese have in any city.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

The release of the information is not neutral. The announcement is hyped up in order to induce the Japanese government to surrender, perhaps before the Soviets enter the war.

HARRY S. TRUMAN (archival):

We have spent more than $2 billion on the greatest scientific gamble in history, and we have won.

GREG MITCHELL:

The goal was to briefly announce the use of the bomb and then describe the existence of the Manhattan Project, which would also be a bombshell for the American public.

HARRY S. TRUMAN (archival):

What has been done is the greatest achievement of organized science in history.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

It was really core that people suddenly know what had happened because that was the sort of propaganda effect. That was going to be all the psychological effect.

This was this moment in which they were going to go from total secrecy to partial openness.

NARRATION:

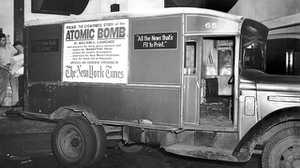

William Laurence’s months-long work suddenly hits front pages nationwide,

and would dominate the news for weeks to come.

GREG MITCHELL:

Laurence had written 14 press releases that were ready for release in a kind of a publicity blitz.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Newspapers hungered for these press releases, and they disseminated them mostly verbatim.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

They're military press releases that are being sort of laundered through the press to make it look like it's organic independent reporting.

GREG MITCHELL:

Laurence was very upset that many of his press release articles appeared without his byline.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

Part of the PR effort was not just to explain it to people but to control what people learned.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

So the philosophy was, let's given everything we think it's safe and useful.

And maybe that will satisfy their appetites and keep them from digging into places we don't want them to.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

The editors loved it. They wanted this information. They wanted to get it out. They knew the public wanted it, and so they did not raise any issues about, well, this is government propaganda. Where's the other side of the story?

MATTHEW DELMONT:

When you look at white newspapers after the bomb was dropped, they're basically just taking what the war department publishes and publishing that. So there's very little variety or nuance.

NARRATION:

The Black Press publishes the official narrative. But it also discovers stories overlooked by the mainstream press.

MATTHEW DELMONT:

There's a sense of pride that shows up in those articles about the intelligence of these Black scientists.

PAUL ALKEBULAN:

When the bomb was first dropped, you're going to have stories about Black scientists participating in the research on the bomb and participating in making of the bomb.

MATTHEW DELMONT:

This is a moment where Black Americans are striving to break new boundaries and get entry into different professions.

But what does it mean to integrate a profession that's about causing devastation at this scale?

Archival Black woman turning newspaper pages

NARRATION:

Shortly after the Hiroshima strike, Black leaders raise their voices.

PAUL ALKEBULAN:

They're going to view the dropping of the bomb through a racial lens. And there's no reason why they wouldn't. If something bad was going to happen, it's going to happen to us first, right? If there's a bomb and it's going to be used, it's going to be used on a person of color first.

FELECIA ROSS:

The Japanese were people of color, just like they are. And so there is an understandable skepticism.

MATTHEW DELMONT:

One of the first to comment on the bomb was Langston Hughes, the great Black poet and writer. He had a column in Black newspapers called Jesse B. Simple, kind of folk hero character that didn't have traditional education but had kind of folk wisdom.

VINCENT INTONDI:

Jesse B. Semple asked the questions that maybe nobody else wants to ask. He says, "We didn't want to use this on white folk. We used this on colored folks. We used this on Japs."

That is the same conversation most likely that's happening in households throughout the Black community.

MATTHEW DELMONT:

Black intellectuals and political leaders are outraged by the dropping of the bomb. Zora Neale Hurston called Truman the butcher of Asia. And W.E.B. Du Bois called Truman one of the greatest killers of our time.

VINCENT INTONDI:

W.E.B. Du Bois says that the merging of science and technology should be a good thing for the world. This is the opposite.

The government has used science and technology and so it's for the worst thing of mankind.

And he says, "What we have done will set back the progress of ‘colored nations for decades to come.’”

NARRATION:

Black intellectuals are not alone in raising alarms about the bomb’s effects...

GREG MITCHELL:

Harold Jacobson was a junior Manhattan Project scientist at Oak Ridge. No big deal, no key figure. But in August, he wrote an article that got a great deal of attention. Hiroshima to be uninhabitable for 70 years.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

That's not the story the U.S. military wanted out.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

Groves wants to argue that it's not radioactivity that does the killing. The killing is caused by a big explosion.

This is a different kind of big explosion, and it's really special, but it's not repulsively special.

GREG MITCHELL:

And here is Jacobson, one of our own scientists, saying Hiroshima would be uninhabitable for 70 years. I'm not quite sure how he arrived at exactly 70, but it made a great headline.

NARRATION:

Jacobson's prediction, which turns out to be inaccurate, doesn't garner nearly as much public attention as the government's heavy-handed response.

GREG MITCHELL:

They got a statement from Robert Oppenheimer, saying that the lingering radiation would be minor.

JANET BRODIE:

Oppenheimer was complicit in tamping down the radiation.

I think he had hopes that atomic weapons could be contained after the war. I think he was denying the same thing that so many scientists were.

They just didn't want to be connected to chemical warfare.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Jacobson was certainly overstepping his knowledge, that's for sure.

But the rebuttal, if it had been a little bit more truthful, would have said, “We don't really know, but we're pretty sure that isn't the case.” And they didn't quite do that. This is the first real challenge they have to their control over the narrative of the bomb.

CRYSTAL UCHINO:

Leslie Nakashima was a popular and celebrated Japanese-American journalist in pre-war Hawaii.

He worked primarily as a sportswriter, but he also covered culture and politics as well. Nakashima's parents both came from a very small fishing village in Hiroshima prefecture. And his father was part of the first wave of contract workers to work on Hawaii's sugar plantations.

Many migrant workers had never intended to stay. This is the case for Leslie Nakashima's parents. They moved back to Japan in the 1930s.

And Nakashima gets offered a job working for the United Press in Tokyo.

But when Pearl Harbor is bombed, Nakashima is out of a job and he starts working for the Japanese Press. So, he actually learns about the atomic bombing before the general public does.

And at the time, his mother was still living in Hiroshima. He immediately books the first train ticket he can get.

The first thing he sees when he arrives at Hiroshima Station is a sea of destruction. He finds his mother alive. He knows this is a really big story. He instinctively starts to record what he's seeing. He's looking out and he sees this city of 300,000 people that, as Nakashima said, had vanished.

He also visits a school near his mother's house that had been turned into a makeshift hospital. And he writes that every day there's two or three people that are dying there. And not only that, but the majority of the cases that are being treated there are considered to be hopeless.

NEWSREEL (archival):

Nagasaki, target for the second atomic bomb. Just three days after Hiroshima, this explosion…

GREG MITCHELL:

Before the Japanese leadership in Tokyo and the Emperor had time to learn about and ponder the first one, the plutonium bomb was used against Nagasaki.

So it really was a, as the U.S. press put it at the time, the one-two punch, the one-two knockout blow.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

William Laurence was on one of the chase planes that followed the bomber over Nagasaki.

WILLIAM LAURENCE (archival):

I saw a great city disappear in a mushroom cloud.

GREG MITCHELL:

The New York Times ran his piece about flying to Nagasaki on the mission.

NARRATION:

The paper proudly advertises Laurence’s role in the Manhattan Project

GREG MITCHELL:

He goes from being a chief publicist to almost overnight back at the New York Times and then wins a Pulitzer for writing pieces that are derived from his status at the Manhattan Project.

NARRATION:

Yet the reporter whose first-hand account actually breaks the story, gets overlooked.

CRYSTAL UCHINO:

Leslie Nakashima's story, Hiroshima as I saw it, gets syndicated but gets sort of lost.

What I think are the most interesting parts of his story. The survivors' experiences, many of whom were acquaintances of his from Hawaii, as well as some of the more provocative language about radiation.

Many newspapers choose to excise that out.

There was a question of credibility. So much of it has to do with the anti-Japanese racism of the time.

The New York Times, for example, buries it several pages in.

NARRATION:

Beneath Nakashima's article, the Times cites General Groves, who calls all reports out of Japan pure propaganda.

ARCHIVAL NEWSREEL JAPAN SURRENDER:

The battleship Missouri becomes the scene of an unforgettable ceremony. General of the Army, Douglas MacArthur, supreme allied commander for the occupation of Japan, boards the Missouri. Cameramen and reporters of many countries record this historic moment.

NARRATION:

After the surrender, General Douglas McArthur is determined to keep American journalists far away from the so-called Atomic Cities.

GREG MITCHELL:

One of the first things MacArthur did was enact a strict press code, which applied to American reporters who had to file their articles through his office.

NARRATION:

But at least one reporter defies his order. Chicago Daily Newsman George Weller quietly slips away to Nagasaki to investigate claims of radiation sickness.

GEORGE WELLER’S VOICE (ARCHIVAL):

MacArthur didn't want anyone to go there because this would lead to a lot of very compassionate stories.

GREG MITCHELL:

When he got there, he found pitiful conditions and observed dozens of victims who seemed to be wasting away. And so he wrote about it.

Weller was very patriotic. Didn't have an agenda.

Weller sent his pieces directly to MacArthur's headquarters in Tokyo. MacArthur's office held those stories and they didn't surface for decades.

GEORGE WELLER’S VOICE (archival):

I was going to treat MacArthur as a gentleman and have him see the dispatches first. He had no right to stop this story.

NARRATION:

A month after the blast, Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett catches a train to Hiroshima.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Wilfred Burchett was an extremely enterprising journalist.

He went to places he wasn't supposed to go.

GREG MITCHELL:

Burchett was taken to a leading hospital.

WILFRED BURCHETT’S VOICE (archival):

These people are all in various states of physical disintegration. Then the flesh started to rot and then gradually bleedings, which they couldn't stop, and then the hair falling out. And the hair falling out was more or less the last stage.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

People were dying in a horrible, painful way that Americans back home were being told wasn't going on.

GREG MITCHELL:

Burchett’s article appeared in the British press and then reprinted around the world with the headline, "The Atomic Plague."

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Burchett's articles were not published in the U.S. They had to be published overseas in papers that were not subject to the rules that the government was laying down for U.S. journalists.

GREG MITCHELL:

Groves was tremendously concerned about batting down claims of radiation disease.

NARRATION:

Groves calls Dr. Charles Rea, hospital director at Oak Ridge, who has no expertise in radiology.

GREG MITCHELL:

And a transcript has emerged, which is horrifying in many ways.

Groves: "The Japs said that “three days after the bomb fell, there were 30,000 dead, and two weeks after the death toll had mounted to 60,000 and is continuing to rise

The doctor at Oak Ridge does agree with Groves that the Japanese, no doubt, are exaggerating, that the people really aren't dying from radiation.

JANET BRODIE:

It's interesting why Groves did this. Rea was not an important part of the Manhattan Project.

He was not a known radiologist. It shows how distraught Groves was about the way the bomb was being seen.

ARCHIVAL ATOMIC BOMB SITE INSPECTED NEWSREEL (archival):

A star-shaped crater marks the New Mexican desert near Alamogordo where the first atomic bomb was tested. Press representatives get a personally conducted tour by General Groves.

NARRATION:

Alarmed by the growing accounts of radiation sickness, Groves invites friendly reporters to visit the Trinity site as further proof of no lingering radiation.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Groves invited a number of journalists, including Laurence, to show that there's no problem. Radiation, what do you mean?

GREG MITCHELL:

Geiger counters were brought out. The readings are relatively low.

And so what are the Japanese talking about? That's how it was reported.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Laurence thinks he is telling you the right story. Everything he writes about how amazing this project is, Laurence believes this. He is a true believer.

FELECIA ROSS:

Meanwhile, in Hiroshima, there's a press junket organized by the military to negate what they're calling Japanese propaganda of lingering radiation effects.

NARRATION:

After covering the surrender in Tokyo the pioneering African American journalist Charles Loeb turns his attention to Hiroshima.

CHARLES LOEB’S VOICE (archival):

After the occupation, I stayed in Japan. We went all over the islands, we went everywhere.

FELECIA ROSS:

Charles Loeb is born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in 1905.

He goes to Howard University and studies pre-med. He was not able to complete those studies because of finances, but he studied it long enough to understand science.

And so he was able to carry that knowledge with him when he joined the Cleveland Call & Post in 1933.

MATTHEW DELMONT:

Loeb was in Tokyo for the surrender ceremonies in 1945, and at that time, a number of the other US journalists traveled to Hiroshima to report on the bomb impact.

When they came back, Loeb described them as being completely flabbergasted.

He didn't take that trip to Hiroshima himself. But Loeb starts with reporting on this history as it was unfolding. Loeb approached it clinically, almost as though he was writing a scientific paper.

He understood and recognized the human cost of it, but he was more focused on the long-term impact of radiation.

PAUL ALKEBULAN:

Charles Loeb wrote that article in the newspaper in 1945, challenging the official story.

And one of the best ways to challenge it was to quote Colonel Stafford Warren, the top physician for the Manhattan Project. Warren was responsible for evacuating Japanese wounded and observing their actions. The best thing he could have done was to say that Warren was the one that was saying, "It's not me, it's not Charles. I'm just a reporter."

MATTHEW DELMONT:

Colonel Warren actually downplays the potential impact of radiation, but Loeb uses it in a very crafty way. Just by the fact that he quotes Warren on this, he introduces the possibility that radiation is present that's impacting Japanese civilians after the bombing.

And so, Loeb structures the entire article in a way that encourages readers to be reckoning with the long-term impacts of the bomb in ways that are years ahead of their time.

NARRATION:

By November, a month after Loeb’s story runs, General Groves can no longer deny that radiation from the bomb is killing people.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

In November 1945, there were a lot of congressional hearings on the Manhattan Project

LESLIE GROVES’S TESTIMONY (archival):

It’s essential that in the highest national interest that further development in the field of atomic energy be pursued…

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

Groves was being asked in particular about the radiation effects, what actually happened.

And he admitted that the Japanese reports of radiation sicknesses were correct.

But Groves tried to put the most positive spin on that that he could. And he reported that according to the experts he talked to, it was a “pleasant” way to die.

JANET BRODIE:

Many people never forgave him for that. And it's colored his reputation.

BEN YAGODA:

The New Yorker was known as a light, humorous magazine.

But as the war went on, people started to take note of the seriousness and extent of the New Yorker war coverage.

NARRATION: In the months following the atomic bombings, the New Yorker commissions an article on Hiroshima.

Editor William Shawn meets with freelance journalist John Hersey.

KAY CALLISON:

Everything written about the bomb at that point was focused on the property damage. That's what they were interested in. Well, John Hersey wasn't like that.

GREG MITCHELL:

When he sat down with William Shawn, he said, "I don't really want to do another piece on the level of destruction. I want to do it on how it affects people."

MICHAEL GORDIN:

John Hersey was a quite remarkable writer with a very long career ahead of him.

BEN YAGODA:

Hersey was born in 1914. He was the son of American missionaries in China.

CALLISON:

Being a mish kid, they're a very distinct kind of person, he thinks.

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

Mish kids, as we call ourselves, are a strange lot. By and large, they turned out either to be very interesting scholars, preachers, doctors, or drunks.

BEN YAGODA:

Hersey was an extremely moral person with humanistic principles. He wasn't religious in the in the conventional sense, but deeply, deeply moral

NARRATION:

By the spring of 1946, America's nuclear program is ramping up, with more testing in the Pacific.

Hersey is finishing up an assignment in China when he learns of pending nuclear tests in the Bikini Atoll.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

Hersey was feeling cold feet about the New Yorker article. He thought, "timing is wrong, and there were going to be more nuclear tests on the Bikini Atoll."

BEN YAGODA:

He wondered and cabled to Shawn whether that might be such an important news peg that writing about Hiroshima would no longer be of interest to people.

Shawn cabled him back and said, "The more time that passes, the more convinced we are that piece has wonderful possibilities. Think it best, time it for anniversary."

NARRATION:

With just four months to go before the anniversary of August 6th, Hersey hops on a naval destroyer for Japan to start his new assignment.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

When Hersey was on the ship, he was sort of thinking, "This is Hiroshima thing. I can't get my mind around how on earth I would do this."

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

While I was on the destroyer, I came down with the flu.

And they brought me some books from the ship's library. One of them was The Bridge of San Luis Rey, which is about five people who are on a rope bridge.

NARRATION:

The novel had just been adapted into a Hollywood film.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

The book weaves together each one's story that led them to be randomly on this bridge at the same moment.

BEN YAGODA:

And a light bulb went off in Hersey's head.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

The bomb. The bomb has a moment when it affects everybody all within a split second.

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

And I saw reading, that a way of approaching Hiroshima by settling on a few people and trying to make their lives real to the reader.

Archival photo John Hersey looking at maps

Journalism would be enriched by using the methods of fiction because the reader can identify with the character and almost feel what the character's experiencing.

BEN YAGODA:

Shortly after getting to Hiroshima, he met Father Kleinsorge, who proved to be a wonderful subject for interview.

One of the things reporters do when they do an interview, they say, who else should I talk to?

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

Father Kleinsorge introduced me to Mr. Tanimoto, the Methodist preacher, and he then introduced me to others.

KAY CALLISON:

He wanted people whose lives had somehow intersected in those immediate days.

BEN YAGODA:

He found his six subjects. Without a doubt, they took to Hersey.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

He doesn't have many of the American prejudices towards East Asians or East Asian societies. He sees them as people. And that's how they appear in the text. They appear as people who are confronted by an enormous horror of war.

KAY CALLISON:

He was telling each person's story in their voice just strictly what happened.

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

“At exactly 15 minutes past 8 in the morning on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.”

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

He's less interested in how they remember it than in reconstructing the experience of having no idea what was going on.

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

“As Mrs. Nakamura started frantically to claw her way toward the baby, she could see or hear nothing of her other children.”

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

You, the reader, are being told for the first time what it's actually like to experience a nuclear bomb blast.

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

“Everything fell and Mrs. Sasaki lost consciousness.

The bookcases right behind her swooped forward and the contents threw her down with her left leg horribly twisted and breaking underneath her.

There in the tin factory, in the first moment of the atomic age, a human being was crushed by books.”

BEN YAGODA:

Hersey comes back and then holes himself away, takes about a month to write this piece.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

He had originally thought he was writing a standard New Yorker piece of about 7,500 words, which is a decent sized length.

But when he started typing, he ended up with 30,000 words.

BEN YAGODA:

The editor had the idea that we published it all in one piece.

So if it was gonna be in one issue, it would have to be the entire issue, which had never happened before.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

Harold Ross, who started the whole thing, liked the idea of emptying the magazine and putting in this one thing, but it was also like, is that too at odds with the larger identity of the New Yorker?

He went back and looked at the original statement of purpose he had put out when he started the magazine in 1925.

And it said, “The New Yorker is an undertaking of serious purpose” and he thought, that's it. Like, serious is enough for me. I can do this.

BEN YAGODA:

The illustration had been commissioned weeks before.

So Ross and Shawn decided that they would put words on the cover.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

Then they sent it off to the printers.

BEN YAGODA:

Shawn sent someone to Grand Central Station to see if people were buying it. He was a little concerned.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

It was people walking past the newsstand and word of mouth within a day sold out the entire newsstand run.

KAY CALLISON:

Everybody at the New Yorker was astonished. Nobody expected this.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

Einstein tried to buy a thousand copies of the magazine and couldn't get any because it sold out the day it hit the stands.

BEN YAGODA:

It was the biggest story of the year. It was written about in all the papers and Time and Newsweek.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

It got immediately turned into a book. This was the sensation of the season.

GREG MITCHELL:

The entire article was read over national radio.

ABC RADIO HIROSHIMA (archival):

“Hiroshima” by John Hersey.

This chronicle of suffering and destruction is broadcast as a warning that what happened to the people of Hiroshima a year ago could next happen anywhere.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

It's written in this very dispassionate way.

ABC RADIO HIROSHIMA (archival):

“And every one of them seemed to be hurt in some way. On some undressed bodies, the burns had made patterns of undershirt straps and suspenders.

And on the skin of some women, the shapes of flowers they had had on their kimonos.”

KAY CALLISON:

He wanted us to see the Japanese as people, not as monsters.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

They're just trying to live their lives and this is the world they happen to live in and then this horrible thing happens to them. To me, that's a profound shift in perspective.

GREG MITCHELL:

Various things that have been done to keep a lid on images from Hiroshima, radiation sickness.

Now in one fell swoop, John Hersey threatened to disrupt that.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

That puts the Truman administration into a bit of a panic and they start to organize a second wave, reinterpreting the narrative of what the bomb means in order to counter Hersey's story.

GREG MITCHELL:

This was a key moment because U.S. nuclear bomb tests were really ramping up. We were on the verge of developing the hydrogen bomb and of course the Soviets were full speed ahead behind us but full speed ahead.

So this was a kind of turning point.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

The audience is the American public that you want not to turn against the nuclear deterrent.

ARCHIVAL SURVIVAL UNDER ATOMIC ATTACK:

If you are at home when a surprise attack occurs, crawl beneath a table if it is very near the window. If the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had known what we know about civil defense, thousands of lives would have been saved.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

You want them to think that nuclear bombs are okay, that we should have them, and that nothing untoward happened when they were used to destroy two Japanese cities.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

So a number of people associated with the Manhattan Project, James Conant, the president of Harvard, General Groves, Secretary of War Stimson, they collaborate and produce this multiple-authored article that's going to come out under Stimson's name and it's going to be the official why we dropped the atomic bomb.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

The United States built this weapon because it was afraid of the Nazis.

Didn't really want to use this weapon but Truman had this choice in front of him. Do we invade Japan?

MICHAEL GORDIN:

There is a very elaborate narrative that such an invasion would have been enormously destructive of American lives.

And even more destructive of Japanese lives.

And so the atomic bomb was a merciful way to end the war with the fewest casualties possible. And that's a way of trying to erode the moral clarity that Hersey is putting forward.

GREG MITCHELL:

Similar to the Hersey piece, Harper's hyped it heavily and it gained a very wide audience, and newspapers reprinted parts of it. And a lot of people said, "Well, we've had our doubts, but this settles it."

Now that we understand why the bomb was used, we don't have to hear about people raising moral issues or something.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

This becomes the definitive way to attack the criticisms by saying it was the lesser of two evils, we agree it was really cruel, but they put us in that position and there was no alternative.

GREG MITCHELL:

So what did we learn from Hiroshima? We should have been able to see the horrible effects on humans and long-term effects, after effects and so forth. But instead, it was like, “Okay, well, we got away with that.”

MICHAEL GORDIN:

The constraints on journalism in the mid ‘40s are overwhelming. So, it's very hard for me to fault the journalists because they're up against a secrecy apparatus that is brand new.

o/c

So they don't even know what they don't know. They don't know where to ask and no one's allowed to talk to them.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

Censorship mostly worked during World War II and after the dropping of the two atomic bombs because General Groves put together a very effective PR effort. One of the odd things is after the bombs were dropped, the war ended, and the effort to control information continued.

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

One of the more creative ways to get even more of this narrative out there is Groves worked with MGM to make a movie about the creation and use of the Atomic bombs.

GREG MITCHELL:

General Groves was the key character in the movie.

THE BEGINNING OR THE END:

Our country must have an atomic bomb. This must be the best kept secret in all history.

GREG MITCHELL:

Anyone who saw it would have seen basically pro-bomb propaganda.

THE BEGINNING OR THE END:

"Mr. President, your press secretary, Mr. Ross, is here."

"And all these advisers tell me the bomb will shorten the war by at least a year.”

“And if the bomb shortens the war, it will save many thousands of American lives."

VINCENT INTONDI:

The American public took the narrative hook, line, and sinker and said, "Okay, we trust the government that this is what was needed. Thank God we got it, and it wasn't another country, and that we have this, and it was the right thing to do."

ALEX WELLERSTEIN:

And this is a remarkably resilient narrative to the point where if you tell somebody this narrative, they'll say, right, that's the story, right? And no, that didn't get really solidified until 1947. So like quite a ways after Hiroshima. And in many ways, it's not true.

There was no deep deliberation over whether to use the bomb. There was no deep concern about the Japanese victims. The plan was to bomb and invade, not one or the other.

The bombs weren’t used to end the war promptly. The bombs were used to scare the Soviet Union into submission. They were not the last salvos of World War II, but the first salvos of the Cold War.

MICHAEL GORDIN:

America sees itself as taking on the mantle of leading the world into freedom.

And the bomb is just an element of that story.

MEN AND IDEAS (archival):

MEN AND IDEAS - HOST (archival):

In this field of science, what would you say was the most exciting event that you have ever reported?

MEN AND IDEAS – WILLIAM LAURENCE (archival):

One night on the desert of New Mexico, July 16, 1945…

o/c

GORDIN:

Into the early 1950s, Laurence continues to fashion himself as an expert on all things nuclear.

MEN AND IDEAS – WILLIAM LAURENCE (archival):

There won't be any wars in the second millenium.

MEN AND IDEAS - HOST (archival):

You think war can be eliminated?

MEN AND IDEAS – WILLIAM LAURENCE (archival)

I think so. I think science is going to make it unnecessary.

VINCENT KIERNAN:

Laurence became known as Atomic Bill. He did other things for the Times. He continued to write other science stories, but his brand was the atomic bomb.

In a lot of ways it is a sad legacy. He was a journalist who was in a singular moment with singular access and he squandered it.

FELECIA ROSS:

After Loeb leaves Japan, he returns to Cleveland where he serves as a managing editor of the Cleveland Call and Post. He is called the Dean of Black Journalism.

VINCENT INTONDI:

Without Charles Loeb, you don't get the Black journalists that you have today. You don't get the reporting that you have today. It's one giant long struggle for freedom. And Charles Loeb is an essential piece of that.

PHILIP GOUREVITCH:

John Hersey wrote one of the most important pieces of reporting from the war and of a defining new event in world history.

MITCHELL STEPHENS:

This was a patriotic American reporting on the horrors that the United States had caused. That's journalism at its most important.

JOHN HERSEY’S VOICE (archival):

If people knew or could imagine what it was like to be one of the survivors and then on top of that realized that a nuclear weapon. 2,900 times as powerful as the Hiroshima bomb has been tested. Then I think that memory would have moved us much faster toward getting rid of these weapons.

NARRATION:

In 1952, seven years after the atomic bombings, the U.S. occupation of Japan ends and censorship is lifted.

NARRATION:

Americans finally get to see what the attacks looked like from the ground, a view they had never seen before.

NARRATION:

LIFE magazine publishes Yoshito Matsushige’s photographs in a special spread.

GREG MITCHELL:

One of Matsushige’s most famous photos is a picture of people on a bridge leading into Hiroshima and you can still see this dust cloud down the road.

And so the symbolic value to me was always that, ever since that day we've all been on that road to Hiroshima -- this nuclear threat that we’ve lived with since 1945.

Bombshell

Bombshell